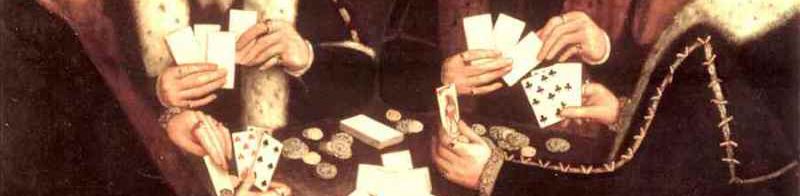

Dice Playing – Image from a Manuscript ca 1524, Tours, France

Article by Baron Aurddeilen-ap-Robet

Raffle: The game being played in the image above is called “raffle,” a game won by rolling three matching numbers at once, similar to modern slot machines. There seems to be some debate over the winning throw of three 3s, for both players point at the dice, but the peddler’s smile suggests he has the upper hand over his disgruntled wealthy opponent. Perhaps he is using weighted dice, a common trick still used today.

Inn and Inn: The period rules for this dice game are described in the 1670 book “Compleat Gamester”. However, the period description is a bit ambiguous, and many of the reconstructions I have seen do not, in my opinion, reflect what the author intended. So I have made my own reconstruction which has been extensively play tested at Pennsic, and other SCA events. Inn and Inn is played in rounds. Each player has the opportunity to roll once each round. Play begins with all players placing an ante of one coin into a common pot. Each player then take turns rolling 4 dice. If they roll a double of any kind, they are considered “INN”, and remain in the game; If they do not, they are “OUT” for the remainder of the game. If at anytime a player rolls a pair of doubles they are considered “INN & INN”, and all following players for the current round, and any future rounds must also roll a pair of doubles, or they are “OUT” for the remainder of the game. Once the dice have been passed around to the all the players, one round is complete and a new round begins. All players that remain in the game place another coin in the pot, and begin taking turns rolling again. The last player that remains in the game is the winner and claims the entire pot. Note: rolling a triple counts the same as a double.

Hazard: is an early English game played with two dice; it was mentioned in Geoffrey Chaucer‘s Canterbury Tales in the 14th century.

Any number may play, but only one player – the caster – has the dice at any one time.

In each round, the caster specifies a number between 5 and 9 inclusive: this is the main. He then throws two dice.

- If he rolls the main, he wins (throws in or nicks).

- If he rolls a 2 or a 3, he loses (throws out).

- If he rolls an 11 or 12, the result depends on the main:

- with a main of 5 or 9, he throws out with both an 11 and a 12;

- with a main of 6 or 8, he throws out with an 11 but nicks with a 12;

- with a main of 7, he nicks with an 11 but throws out with a 12.

- If he neither nicks nor throws out, the number thrown is called the chance. He throws the dice again:

- if he rolls the chance, he wins;

- if he rolls the main, he loses (unlike on the first throw);

- if he rolls neither, he keeps throwing until he rolls one or the other, winning with the chance and losing with the main.

This is simpler to follow in a table:

| Main |

Nicks |

Outs |

Chance |

| 5 |

5 |

2,3,11,12 |

Anything else |

| 6 |

6,12 |

2,3,11 |

| 7 |

7,11 |

2,3,12 |

| 8 |

8,12 |

2,3,11 |

| 9 |

9 |

2,3,11,12 |

The caster keeps his role until he loses three times in succession. After the third loss, he must pass the dice to the player to his left, who becomes the new caster.

Shut the Box: Though this game is very fun to play, and is readily available to be purchased from modern sources, there is no documented or physical evidence that “Shut the Box” is a medieval game.

14th Century Dice – Image courtesy of the Journal for Archaeology of the Low Countries, Belgium

Riffa (3 dice, 2 or more players)

All players put down a stake on the table to form a pot. Players roll high die to see who goes first, then play proceeds clockwise around the table. Players take turns rolling 3 dice until they roll a pair. When that happens the pair is set aside and the player re-rolls the third dice. The value of the third die is added to the value of the pair and that is the player’s score for the round. Once all the players have had a turn the round ends and the scores are compared; the highest score wins the pot.

As Many on One as of Two (3 dice, 2 or more players)

All players put down a stake on the table to form a pot. Players roll high die to see who goes first, then play proceeds clockwise around the table. The first player rolls one die first and takes note of the value. They then have to match that value by rolling the other two dice. So if the first dice is a 5, then the player must roll 1&4 or 2&3. The First player to match their first roll wins the pot. If they do not match, then the dice pass to the next player. If everyone has a turn and no one matches on the first round, then additional coins are added to the pot by each player and the next round begins.

Pair and Ace (3 dice, 2 or more players)

All players put down a stake on the table to form a pot. Players roll high die to see who goes first, then play proceeds clockwise around the table. Each player takes turns rolling the dice. The first player to roll a pair on two dice plus a 1 on the third dice wins the pot. If everyone has a turn and no one rolls a pair and a 1, then additional coins are added to the pot by each player and the next round begins.

Triga (3 dice, 2 or more players)

All players put down a stake on the table to form a pot. Players roll high die to see who goes first, then play proceeds clockwise around the table. The first player to roll a 15, 16, 17, 18, or 3,4,5,6 or a triple of any value wins the pot.

Passe-dix or Passage (3 dice, 3 or more players)

Passe-dix was specified by Matthew’s gospel (Matthew 27:35) as the dice game the Roman guards played under the site of the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth. Known as Passage in English.

Pass-dix begins with the Caster rolling a single die. The players then decide what they believe will

be the outcome of rolling another die. Will it (A) equal 10, or lower, or (B) total 11, or higher. Each player finds a player who is willing to wager against them, and they negotiate their individual bets. If there are more players wagering on one side than the other, an individual may cover the wagers of more than one opponent, but there is no obligation to do this. If no one is willing to wager on one side, or the other, the Caster re-rolls the first die. Once the bets are placed, the Caster rolls the second die. If the roll of the second die brings the total to 11 or over, the players who wagered on that outcome win, and the third die is not used. If the total is still below 10 the betting partners may increase the wagers if their opponent agrees. (Once the original bets are agreed upon players cannot decrease their original wagers, nor are they allowed to change sides.) The Caster then rolls the third die if necessary, and wagers are settled based on the total of the three dice. The dice are then passed to a new Caster for the next round. The Caster may also make wagers, but except for being the one to roll the dice, the Caster has no advantages over other players.

Additional information on Early Dice Games can be found in the following pdf.

You must be logged in to post a comment.